With How to Apply the Rule of Thirds to Your Paintings at the forefront, this guide opens a window to an amazing start and intrigue, inviting you to embark on a journey of artistic discovery filled with unexpected twists and insights.

Understanding and implementing the Rule of Thirds can dramatically elevate the visual appeal and impact of your artwork. This principle, a cornerstone of effective composition, involves dividing your canvas into nine equal sections, creating a natural framework for placing key elements. By strategically positioning your subjects along these lines or at their intersections, you can create more dynamic, balanced, and engaging paintings that captivate your audience.

Understanding the Rule of Thirds in Composition

The Rule of Thirds is a foundational principle in visual arts, offering a simple yet powerful framework for creating balanced and engaging compositions. It guides artists in placing key elements within their artwork to enhance visual appeal and direct the viewer’s eye. This guideline, while not a strict law, has been instrumental in the success of countless paintings and photographs throughout history.At its core, the Rule of Thirds involves mentally dividing your canvas into nine equal sections by drawing two equally spaced horizontal lines and two equally spaced vertical lines.

These lines create a grid, and the points where they intersect are considered particularly strong areas for placing important compositional elements. This grid acts as a guide, helping to avoid the common pitfall of centering subjects, which can often lead to a static or uninteresting image.

The Grid and Intersection Points

The grid created by the Rule of Thirds consists of four lines: two horizontal and two vertical, spaced one-third of the way from each edge of the canvas. These lines intersect at four distinct points. These intersection points are often referred to as “power points” or “sweet spots” because the human eye is naturally drawn to them. Placing a primary subject or a significant element of your composition on or near these intersection points can create a sense of dynamism and visual interest.

For example, in a landscape painting, the horizon line might be placed along one of the horizontal lines, and a prominent tree or building could be positioned at one of the intersection points.

Historical Context and Origins

The origins of the Rule of Thirds are somewhat debated, with influences tracing back to principles of the Golden Ratio and classical art theory. While the exact inventor is unknown, the concept gained significant traction in the 18th century, particularly within the context of painting and landscape design. Artists and theorists recognized that asymmetrical compositions often possessed a greater sense of harmony and visual appeal than strictly symmetrical ones.

In photography, the rule was widely adopted with the advent of more accessible cameras, becoming a standard teaching tool for beginners and a valuable technique for experienced photographers alike. It’s believed to have been popularized by Sir John Herschel in the mid-19th century.

Psychological Impact of Off-Center Placement

Placing subjects off-center, as suggested by the Rule of Thirds, has a profound psychological impact on the viewer. A subject placed directly in the center can feel static, confronting, and sometimes even confrontational. Conversely, an off-center subject creates a sense of movement and visual flow. It encourages the viewer’s eye to explore the rest of the composition, seeking context and narrative within the surrounding space.

This off-center placement can also create a sense of anticipation or imply movement, as if the subject is about to enter or has just exited the frame. The negative space created around the subject becomes just as important as the subject itself, contributing to the overall mood and storytelling of the artwork.

“The Rule of Thirds is not a law, but a guideline. Its purpose is to help create more dynamic and visually engaging compositions by encouraging the placement of key elements off-center.”

Practical Application for Painters

Understanding the Rule of Thirds is one thing, but effectively applying it to your canvas is where the magic truly happens. This section will guide you through the tangible steps to integrate this compositional guideline into your painting process, transforming your visual storytelling and creating more engaging artworks. We will explore methods for visualizing and implementing the grid, strategically placing your focal points, and balancing your compositions with horizons and vertical elements.By consciously employing the Rule of Thirds, you can move beyond accidental pleasing arrangements and develop a deliberate approach to composition that enhances the viewer’s experience.

It’s about guiding the eye, creating visual interest, and imbuing your paintings with a sense of dynamic balance.

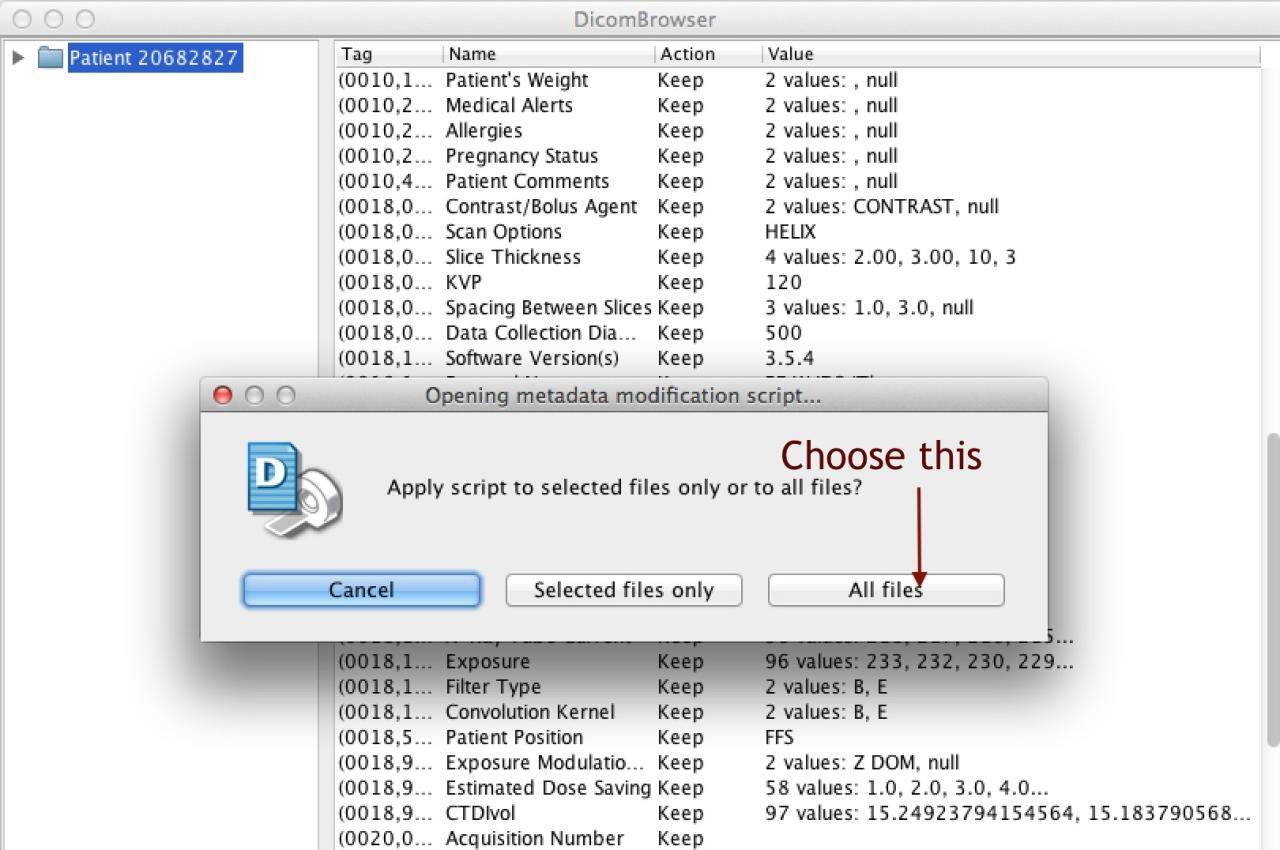

Mentally or Physically Overlaying a Grid

Before you even touch your brush to the canvas, or at any stage of your painting, you can utilize a grid to guide your composition. This can be done with varying degrees of precision, from a quick mental sketch to a more defined physical overlay. The goal is to break down your canvas into nine equal sections, creating a framework for placing key elements.There are several effective methods for applying this grid:

- Mental Visualization: As you begin sketching or planning your painting, imagine two equally spaced horizontal lines and two equally spaced vertical lines dividing your canvas. Practice this frequently, and soon you’ll be able to “see” the grid superimposed on any surface.

- Sketching the Grid: On your preliminary sketches or directly onto your canvas with a light pencil or charcoal, draw the grid lines. This provides a tangible guide to refer to as you paint. Ensure the lines are faint enough to be easily covered by paint.

- Using a Physical Overlay: For digital art or photography, a digital grid can be easily applied. For traditional painting, you can create a transparent overlay (like acetate or tracing paper) with the grid drawn on it, which you can then place over your reference image or even your canvas.

- Proportional Measurement: If your canvas is 24 inches wide, divide it by three to get 8 inches. Your vertical lines would then be at the 8-inch and 16-inch marks. Similarly, for a 30-inch tall canvas, divide by three to get 10 inches, placing your horizontal lines at the 10-inch and 20-inch marks.

Positioning the Main Subject on Intersection Points

The intersection points of the grid are arguably the most powerful areas within the Rule of Thirds. These four points naturally draw the viewer’s eye, making them ideal locations for your primary subject or focal point. Placing your subject here creates immediate visual interest and anchors the composition.Consider these approaches when placing your main subject:

- Direct Placement: If your subject is a single object, like a portrait’s eyes, a flower, or a lone tree, aim to align a significant feature of that subject with one of the four intersection points. For instance, in a portrait, the subject’s dominant eye could be placed on an upper-left or upper-right intersection.

- Implied Placement: Even if the subject itself doesn’t perfectly align, its gaze, gesture, or most important feature can point towards or emanate from an intersection point. This creates a sense of directed energy and narrative.

- Multiple Subjects: If you have a few key elements, you can distribute them across different intersection points. However, be mindful of creating a hierarchy; one point should still feel more dominant to avoid a scattered composition.

Placing Horizons or Strong Horizontal Elements

Horizons, or any significant horizontal lines within your painting, are best placed along the upper or lower horizontal grid lines. This simple adjustment can dramatically alter the mood and emphasis of your artwork. Placing the horizon higher can emphasize the foreground, while placing it lower gives more prominence to the sky or background.Here’s how to effectively use horizontal lines:

- Sky Dominance: Position the horizon on the lower horizontal line (approximately one-third of the way up from the bottom) to give two-thirds of your canvas to the sky. This is effective for dramatic cloudscapes, expansive skies, or when the sky plays a crucial role in the narrative.

- Foreground Emphasis: Conversely, placing the horizon on the upper horizontal line (approximately one-third of the way down from the top) dedicates two-thirds of the canvas to the land or foreground. This is ideal for landscapes where the terrain, details on the ground, or the journey through the scene are paramount.

- Balanced Composition: If neither the sky nor the foreground demands dominance, centering the horizon on the middle horizontal line can create a more stable and balanced feel, though it can sometimes feel less dynamic than adhering strictly to the one-third rule.

Aligning Vertical Elements

Vertical elements, such as trees, buildings, figures, or even strong architectural lines, gain strength and presence when aligned with the vertical grid lines. This creates a sense of order, stability, and visual direction within the painting.Methods for aligning vertical elements include:

- Single Vertical Subject: If your painting features a prominent vertical element, such as a tall tree or a solitary figure, position it directly along one of the two vertical lines. This anchors the element and gives it visual weight.

- Multiple Vertical Elements: When you have several vertical elements, you can distribute them across the vertical lines to create rhythm and depth. For example, a row of trees could be spaced to align with or fall between the vertical lines, creating a sense of recession.

- Guiding the Eye: Vertical lines can also be used to lead the viewer’s eye through the composition. A pathway, a fence, or even the implied line of a figure’s posture can be aligned with a vertical grid line to direct attention towards the main subject or a point of interest.

Strategic Placement of Elements

The Rule of Thirds is more than just a guideline for placing your subject; it’s a powerful tool for orchestrating the entire visual experience of your painting. By understanding how to strategically position elements, you can create a sense of balance, direct the viewer’s attention, and imbue your artwork with a dynamic energy that resonates. This section delves into the practical application of the grid for achieving these compositional goals.The grid, with its intersecting points and dividing lines, provides a framework for distributing visual weight and creating a harmonious arrangement.

Think of these intersections and lines as magnets for attention, drawing the viewer’s eye and creating points of interest. Properly utilizing these areas ensures that your painting feels stable yet engaging, avoiding a sense of being too crowded or too empty.

Balancing Visual Weight with the Grid

Visual weight refers to the perceived importance or “heaviness” of an element within a composition. A well-balanced painting feels stable, with elements distributed in a way that prevents one area from overwhelming another. The Rule of Thirds grid is instrumental in achieving this balance.

- Distributing Focal Points: Place your primary subject or points of interest on or near the intersections. If you have multiple elements, consider placing them on different intersections to create a visual dialogue between them. For instance, a portrait might have the subject’s eyes on one intersection, while a significant object in the background could be placed on another, creating a layered sense of importance.

- Symmetrical vs. Asymmetrical Balance: While placing subjects symmetrically on opposite intersections can create a formal balance, asymmetrical balance, achieved by placing elements on different third-line intersections, often leads to a more dynamic and engaging composition. This is because the viewer’s eye has to travel more to connect these elements, creating a sense of movement.

- Varying Element Size and Value: The visual weight of an element is also influenced by its size, color saturation, and value (lightness or darkness). A large, dark, or brightly colored object will naturally carry more visual weight than a small, light, or desaturated one. Use the grid to strategically place these heavier elements, balancing them with lighter or smaller elements placed on other parts of the grid or within the negative space.

Enhancing Focus with Negative Space

Negative space, the area surrounding and between your subject(s), is just as crucial as the positive space your elements occupy. When used in conjunction with the Rule of Thirds, negative space can significantly amplify the impact of your focal points.

Negative space is not empty space; it is an active element that defines and accentuates the subject.

- Defining the Subject: By allowing ample negative space around a subject placed on an intersection, you isolate it and draw immediate attention. This is particularly effective for single subjects, such as a lone tree against a vast sky or a portrait with a simple, uncluttered background.

- Creating Depth and Atmosphere: Large areas of negative space, especially those aligned with the outer thirds of the grid, can suggest vastness, distance, or a particular mood. For example, a horizon line placed on the top or bottom third line, with a significant portion of the canvas dedicated to sky or land respectively, uses negative space to convey a sense of scale or solitude.

- Guiding the Eye: The shape and placement of negative space can also subtly guide the viewer’s eye towards the focal point. For instance, a curving path of negative space leading from the edge of the canvas towards a subject on an intersection can create a natural flow.

Guiding the Viewer’s Eye with Lines and Forms

The grid lines themselves, along with any lines and forms within your painting, can be used to direct the viewer’s gaze through the composition. Aligning these visual pathways with the Rule of Thirds enhances the natural flow and intended reading of your artwork.

- Leading Lines: Roads, rivers, fences, or even the edge of a building can act as leading lines. If these lines naturally converge towards or run along the third lines or intersections, they will effectively guide the viewer’s eye to the points of interest. For example, a path that starts at the bottom left corner and curves towards a subject placed on the top right intersection will lead the viewer’s eye through the entire painting.

- Implied Lines: The direction in which figures are looking or pointing, or the arrangement of elements that suggest a direction, can also create implied lines. Align these implied lines with the grid to reinforce the composition’s structure and direct attention to key areas.

- Shapes and Forms: The placement of dominant shapes and forms can also influence the eye’s movement. A strong diagonal form placed along a third line can create a sense of energy and draw the eye across the canvas. Similarly, a series of smaller forms arranged in a sequence along a third line can create a visual rhythm.

Left-Hand Intersection vs. Right-Hand Intersection

The choice of placing a primary subject on a left-hand intersection versus a right-hand intersection can subtly alter the viewer’s perception and the overall narrative of the painting. This distinction is often related to cultural reading habits, where Western audiences tend to read from left to right.

- Left-Hand Intersection: Placing a subject on a left-hand intersection often suggests that the subject is about to embark on a journey, is looking back, or is in a state of contemplation before action. It can feel more introspective or like the beginning of a narrative. For example, a character looking towards the right side of the canvas from the left intersection implies anticipation or a future focus.

- Right-Hand Intersection: A subject placed on a right-hand intersection can convey a sense of arrival, completion, or looking towards the future. It often feels more resolved or like the culmination of an action. For instance, a character looking towards the left side of the canvas from the right intersection might suggest reflection or a past event.

- Contextual Significance: The surrounding elements and the overall theme of the painting will heavily influence the interpretation. However, understanding this general tendency can help you make deliberate choices to enhance the emotional impact and storytelling within your work. For instance, in a landscape, placing a solitary house on the left intersection might evoke a sense of it being a starting point for a journey, while on the right, it might feel like a settled, established dwelling.

Beyond the Basics: Variations and Considerations

While the Rule of Thirds provides a robust framework for creating balanced and engaging compositions, it is not the only tool in an artist’s arsenal. Understanding its limitations and exploring alternative approaches can lead to even more dynamic and impactful paintings. This section delves into other compositional guides, scenarios where deviating from the Rule of Thirds proves beneficial, its application across various genres, and how canvas dimensions can influence its use.

Alternative Compositional Guides

Beyond the grid of the Rule of Thirds, several other compositional principles can guide your artistic decisions, offering different ways to achieve visual harmony and interest. These methods often complement or provide a different perspective on how to arrange elements within your frame.

- The Golden Ratio (Phi Grid): Similar to the Rule of Thirds, the Golden Ratio uses a grid derived from the mathematical constant approximately equal to 1.618. This grid divides the canvas into sections that are aesthetically pleasing and believed to be naturally attractive to the human eye. The intersection points and lines are considered ideal locations for focal points.

- The Rule of Odds: This principle suggests that compositions with an odd number of subjects or elements are generally more visually appealing and dynamic than those with an even number. An odd number creates a natural asymmetry that encourages the viewer’s eye to move through the composition, seeking resolution.

- Symmetry and Asymmetry: While the Rule of Thirds often leans towards asymmetry, understanding and intentionally employing symmetry can create a sense of order, stability, and grandeur. Conversely, deliberate asymmetry can introduce tension, movement, and a feeling of unease or excitement.

- Leading Lines: This technique involves using natural or man-made lines within the artwork to draw the viewer’s eye towards a specific point of interest. These lines can be roads, rivers, fences, or even the implied lines created by the arrangement of objects.

Effectively Breaking the Rule of Thirds

While the Rule of Thirds is a powerful guideline, there are numerous instances where consciously deviating from it can enhance a painting’s impact. Breaking the rule should be a deliberate choice, serving a specific artistic purpose rather than an accidental oversight.

- Creating Tension and Drama: Placing a subject directly in the center can create a strong sense of confrontation or importance, especially in portraits. This can be used to convey power, introspection, or a direct connection with the viewer.

- Emphasizing Scale or Isolation: A subject placed very close to an edge or in a vast, empty space can heighten the sense of isolation, vulnerability, or the overwhelming nature of the environment. This is particularly effective in conveying a narrative of solitude.

- Achieving a Sense of Movement or Flow: Sometimes, placing a subject off-center in a way that suggests imminent movement or interaction with the surrounding space can create a more dynamic and engaging composition than a static placement.

- Highlighting Specific Relationships: When depicting multiple subjects, a central grouping can emphasize their unity or conflict, while off-center arrangements might suggest separation or differing relationships.

Application Across Painting Genres

The Rule of Thirds, and its variations, can be adapted to suit the unique demands and characteristics of different painting genres. The way elements are arranged will inherently differ based on the subject matter.

Landscapes

In landscapes, the Rule of Thirds is often applied to the horizon line, placing it on the upper or lower third to emphasize either the sky or the foreground. Key elements like trees, mountains, or buildings are strategically positioned on intersection points to draw the viewer’s eye into the scene. For instance, a lone tree might be placed on a third line, with its branches extending into the upper portion of the canvas, balancing the composition.

Portraits

For portraits, the eyes are typically the most important focal point. Applying the Rule of Thirds means placing the eyes on one of the upper intersection points, creating a more engaging gaze. The rest of the subject’s body or background can then be arranged to complement this focal point, ensuring a balanced and aesthetically pleasing portrait. A subject looking off-canvas towards an empty space can also create intrigue and invite the viewer to imagine what they are seeing.

Still Life

In still life paintings, the Rule of Thirds can be used to arrange individual objects or groups of objects. Instead of placing a single vase directly in the center, consider positioning it on a third line, with supporting elements like fruit or drapery arranged on other intersection points or along the lines. This prevents the composition from feeling static and encourages exploration of the entire arrangement.

Influence of Canvas Size and Shape

The dimensions of your canvas can significantly impact how you apply compositional guides like the Rule of Thirds. A large, wide canvas might lend itself to different applications than a small, square format.

- Wide Rectangular Canvases: These formats are excellent for landscapes or panoramic scenes. The horizontal lines of the Rule of Thirds can be used to divide the expansive space, placing the horizon on the lower third to emphasize a vast sky, or on the upper third to focus on the intricate details of the foreground. The vertical lines can help break up the horizontal expanse, guiding the eye across the scene.

- Tall Rectangular Canvases: Ideal for portraits or architectural subjects, these canvases benefit from placing key elements along the vertical third lines. In a portrait, the face might be positioned to one side, allowing for negative space that adds depth or narrative. For architectural subjects, the vertical lines can emphasize height and structure.

- Square Canvases: Square formats offer a more contained and often intimate feel. Applying the Rule of Thirds here can create a sense of balance and harmony. The intersection points are still valuable, but the lack of inherent directional bias means the artist has more freedom to experiment with central placements or more abstract arrangements while still maintaining visual interest.

- Irregular Shapes: For canvases with non-standard shapes, such as triptychs or irregular polygons, traditional grid-based rules might need to be adapted or even set aside. The inherent structure of the shape itself becomes a primary compositional element, and artists might rely more on intuitive placement, color relationships, and the flow of forms to achieve a compelling composition.

Illustrative Examples and Visual Guidance

To truly grasp the power of the Rule of Thirds, let’s explore some practical applications across different painting genres. These examples will help visualize how strategically placing elements can elevate your compositions from ordinary to captivating.

Solitary Tree Composition

Imagine a landscape painting where the viewer’s eye is immediately drawn to a solitary, majestic tree. This tree is positioned precisely at the top-left intersection point of the Rule of Thirds grid. The vast expanse of the sky dominates the upper two-thirds of the canvas, creating a sense of openness and scale. The lower third might feature a subtle hint of rolling hills or a grassy plain, grounding the composition and providing context for the tree’s isolation.

This arrangement emphasizes the tree’s individual presence against the immensity of nature, evoking feelings of solitude, resilience, or quiet contemplation.

Portrait with Strategic Eye Placement

Consider a compelling portrait where the subject’s gaze is the primary focus. In this composition, the subject’s eyes are meticulously aligned with the upper horizontal line of the Rule of Thirds grid. Furthermore, one eye, or perhaps the focal point of the face, is positioned directly on a right-hand intersection point. This placement creates a dynamic and engaging connection with the viewer, as the subject appears to be looking slightly out of the frame, inviting the audience into their world.

The remaining space can be used to suggest environment or simply provide a complementary background, ensuring the subject remains the undisputed hero of the piece.

Winding Path Creating Movement and Depth

Visualize a scene that guides the viewer’s journey through the artwork. A winding path, rendered with subtle shifts in perspective and texture, begins in the foreground and meanders towards a significant focal point. This focal point, perhaps a lone cottage, a distant mountain peak, or a shimmering body of water, is strategically placed on a bottom-right intersection point. The path itself, by following a diagonal line that intersects with other third lines, inherently creates a sense of movement and depth.

The viewer’s eye is naturally led along this visual pathway, experiencing the illusion of traveling through the painted space towards the compelling destination.

Still Life Arrangement with a Primary Object

Envision a classic still life arrangement that feels balanced yet dynamic. A primary object, such as a gleaming ceramic vase or a ripe piece of fruit, is placed with its center of interest on a lower-left intersection point. This anchors the composition and provides a strong starting point for the viewer’s exploration. Supporting elements, such as complementary fruits, scattered fabric, or delicate flowers, are then thoughtfully distributed within the surrounding thirds of the canvas.

This distribution avoids a static, centered arrangement, instead creating visual interest and a sense of narrative as the eye moves from the primary object to its supporting cast, enhancing the overall harmony and storytelling of the still life.

Final Review

In essence, mastering the Rule of Thirds is about more than just placing objects; it’s about orchestrating visual harmony and guiding the viewer’s experience. Whether you’re a seasoned artist or just beginning your creative journey, incorporating this fundamental principle can unlock new levels of expressiveness and sophistication in your work, transforming ordinary scenes into extraordinary compositions that resonate long after the brushstrokes have dried.